If you are an international medical graduate (IMG) dreaming of a residency position in the United States, you have likely heard one phrase more than any other: U.S. clinical experience. This single line on your application can feel like the golden ticket, but it also brings a ton of confusion. What exactly are program directors looking for? Does shadowing count? What about that research position at a famous hospital? The question, “What counts as U.S. clinical experience?” is arguably the most critical one for IMGs to answer correctly. Getting it wrong can mean wasted time, money, and a weaker application.

The truth is, not all experience labeled “clinical” holds the same weight. In the competitive arena of residency matching, U.S. clinical experience is your proving ground. It is your chance to demonstrate that you can not only understand the American healthcare system but also thrive within it, communicate effectively with patients and teams, and apply your medical knowledge in a real-world setting. This guide will cut through the ambiguity, clearly defining what truly counts, what does not, and how you can build the strongest possible case for your skills and adaptability.

Defining “U.S. Clinical Experience” in Plain English

Let us start with a simple definition. For an IMG’s residency application, U.S. clinical experience refers to any direct, structured exposure to patient care within the American healthcare system that is documented and can be verified by a U.S. licensed physician. The core purpose is to prove your clinical competence, professionalism, and familiarity with U.S. medical protocols.

However, the real magic lies in the intent behind this requirement. Residency program directors use this experience to answer several vital questions about you: Can this doctor communicate clearly with American patients and nurses? Do they understand workflows in a U.S. hospital? Can they handle the pace and documentation? Do they fit culturally within a medical team? Therefore, the experience that “counts” the most is the kind that provides clear, positive answers to these questions. It is less about just being present and more about actively participating in a way that you can later discuss convincingly in your personal statement and interviews.

The Gold Standard: Hands-On Clinical Externships and Clerkships

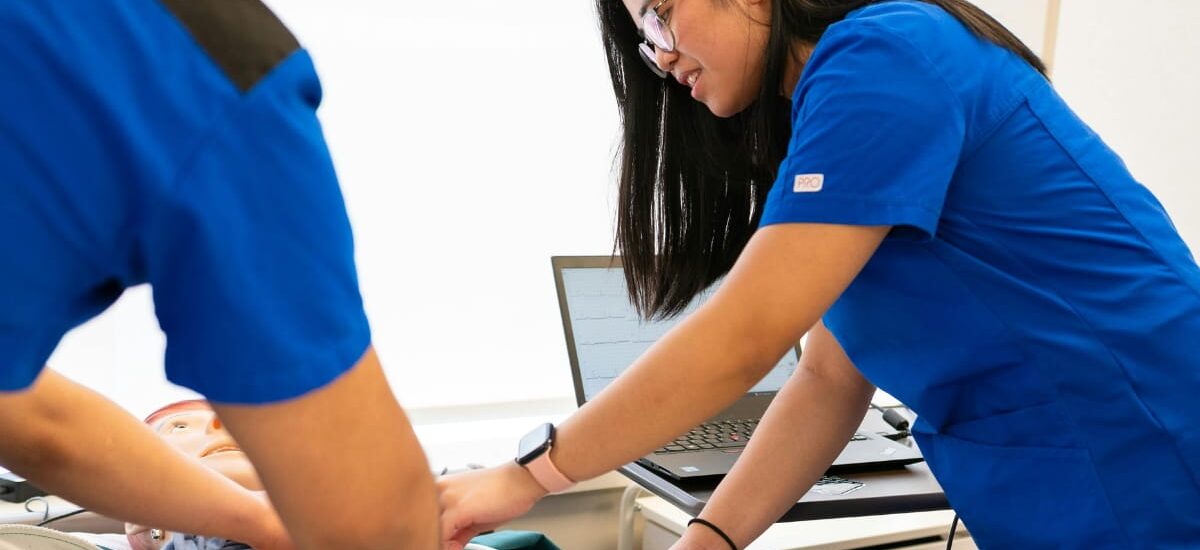

When we talk about the most valuable type of experience, we are referring to hands-on clinical roles. These are the activities that make program directors take notice because they most closely mimic the responsibilities of an actual resident.

Clinical Externships (sometimes called Sub-Internships or Acting Internships): This is often the top tier. In an externship, you typically function at the level of a senior medical student or an intern. Your duties are hands-on; you take patient histories, perform physical exams, present cases to attending physicians, write progress notes (often co-signed), and participate in rounds. You are an integrated part of the team. This experience provides powerful stories for your interviews and generates compelling letters of recommendation from U.S. physicians who have seen you work.

U.S. Medical Clerkships/Electives: These are rotations completed through a U.S. medical school, often by students in their final year. For IMGs, accessing these can be challenging but not impossible through specific exchange programs or university-affiliated opportunities. Like externships, they offer direct patient care responsibilities and are highly respected because they occur within the standard U.S. medical training pathway.

The key element for both of these is active participation and documentation. You are not just watching; you are doing, and your involvement is reflected in official paperwork and evaluations.

The Middle Ground: Observerships and Research with Patient Contact

Some experiences offer valuable exposure but fall short of the hands-on ideal. They can still be beneficial, especially if you lack any U.S. exposure, but you must understand their limitations.

Clinical Observerships: In an observership, you shadow a physician. You follow them on rounds, into clinics, and during procedures, but you have no direct patient care responsibilities. You do not touch patients, write notes, or present cases. While this is excellent for learning hospital culture and medical workflows, it provides little evidence of your own clinical skills. Listing it as “clinical experience” without clarification can be a red flag. It is better to label it honestly as an “observership” and focus on what you learned about the system, communication, and diagnostics.

Clinical Research with Patient Contact: This can be a unique and strong option. If your research role involves direct interaction with patients—such as enrolling subjects, explaining protocols, or collecting clinical data—you gain valuable experience. You demonstrate an understanding of ethics (IRB), patient consent, and data management within the U.S. system. However, you must clearly articulate the clinical component of your research, as pure lab-based research does not count as clinical experience.

What Does NOT Count as Meaningful U.S. Clinical Experience

To avoid costly mistakes, it is crucial to know what experiences do not fulfill the intent of the requirement. Be wary of considering the following as your primary clinical experience:

- Pure Shadowing with No Structure: Casual, undocumented shadowing of a family friend who is a doctor provides no verifiable evaluation or meaningful depth.

- Non-Clinical Work in a Hospital: Working as a secretary, IT staff, or even a scribe who only documents without clinical input does not demonstrate your medical skills. Medical scribing can be a gray area; if it involves real-time clinical decision-making discussions with the physician, it might be framed as an observational learning experience, but it is not a substitute for an externship.

- Online Courses or Simulated Experiences: While these can enhance knowledge, they do not replace real human interaction in a clinical setting.

- Experience from Your Home Country: No matter how extensive, your home country residency or work is not U.S. clinical experience. The requirement is specifically designed to assess your function within the U.S. context.

How to Secure the Right Kind of U.S. Clinical Experience

Finding these opportunities requires a proactive strategy. Start by networking relentlessly. Reach out to alumni from your medical school who are now in the U.S. Contact physicians in your desired specialty, sending a concise, professional email expressing your goals. Many universities and teaching hospitals have formal observership or externship programs for IMGs—research these diligently.

Furthermore, when you secure a position, maximize it. Treat every day as a long interview. Be eager, professional, punctual, and engaged. Build genuine relationships with attendings and residents. Most importantly, well before your rotation ends, ask your supervising physician for a Letter of Recommendation. A strong, detailed LOR from a U.S. physician who has directly supervised your clinical work is the single most valuable output of your experience and is tangible proof that you excelled in a U.S. setting.

Presenting Your Experience Powerfully on Your Application

How you describe your experience on your ERAS application is almost as important as the experience itself. Use action verbs that convey responsibility: “Performed,” “Presented,” “Assessed,” “Documented,” “Collaborated.” Be specific about your patient interactions and your role on the team.

Instead of: “Did an observership in Internal Medicine.”

Write: “Completed a hands-on clinical externship in Internal Medicine at XYZ Hospital, performing histories and physicals on new admissions, presenting cases on daily rounds, and contributing to treatment plan discussions under the supervision of Dr. Jane Smith.”

This language clearly signals a participatory role. Also, categorize your experience correctly in the ERAS sections to avoid any perception of misrepresentation.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Does an observership count as U.S. clinical experience?

It counts as U.S. exposure, but not as hands-on clinical experience. You should include it on your application, but clearly label it as an “Observership” and focus on the insights you gained into the U.S. system, rather than claiming patient care duties you did not have.

How many months of U.S. clinical experience do I need?

There is no official rule, but quality trumps quantity. Even 2-3 months of a strong, hands-on externship with excellent letters of recommendation is far more valuable than 6 months of passive observerships. Most successful IMGs have at least 3-6 months of meaningful experience.

Is paid clinical experience better than unpaid?

For residency applications, the status (paid/unpaid) is irrelevant. What matters is the hands-on nature, the quality of supervision, and the strength of the recommendation letter it produces. Do not turn down a superb unpaid externship for a paid non-clinical job.

Can telemedicine experience count?

This is an emerging area. If the telemedicine role involves direct, real-time patient assessment, diagnosis, and treatment planning under U.S. licensure, it may hold some weight. However, traditional in-person experience is still preferred as it demonstrates broader team integration and physical exam skills.

What if I only have research experience in the U.S.?

You should list it accurately as research. To strengthen your application, you will need to complement it with actual clinical experience. You can leverage your research connections to help you find a clinical preceptor.

Conclusion: It’s About Proof, Not Just Presence

Ultimately, the question of what counts as U.S. clinical experience centers on proof. Residency programs need proof that you will not struggle with the fundamentals of practicing medicine in America. The best proof is a verifiable, hands-on role where you performed core clinical tasks, coupled with a glowing recommendation from a U.S. physician who can vouch for your abilities.

Therefore, your goal is not merely to “get” U.S. experience. Your goal is to seek out the most hands-on, participatory, and evaluative opportunity you can find. Invest your time and resources into securing an externship where you can be an active team member. Then, excel in that role with professionalism and enthusiasm. That specific type of experience does not just “count”. It becomes the cornerstone of your entire application, convincingly telling program directors that you are not just ready for the U.S. healthcare system, but that you are already a part of it.